“I am a street photographer, that is where I am myself. As a journalist as well as a photographer, I do not invent but I search, I investigate and catch it.”

BIOGRAPHY

Giulio Obici was born in Venice in 1934 and was special correspondent and editor of Paese Sera. During the years of upheaval and terrorism he concentrated his investigations on the counter information about massacres, the corrupt secret service, dark plots and political trials. He also spoke about the decline of the First Republic, not only following but often forecasting the judicial investigations on Italian mysteries.

Giulio Obici was born in Venice in 1934 and was special correspondent and editor of Paese Sera. During the years of upheaval and terrorism he concentrated his investigations on the counter information about massacres, the corrupt secret service, dark plots and political trials. He also spoke about the decline of the First Republic, not only following but often forecasting the judicial investigations on Italian mysteries.

Apart from being a journalist, he always had a deep love for photography, capturing in black and white the surreal dimensions of everyday life; searching for the image that could evoke and synthesize a story of life or to make sense of the chaos of reality. That was the aim in 1954: a photograph telling a story.

Obici used a Leica M and printed his own photographs.

He published the essay Venezia fino a quando? (Venice until when?) (1967) and the photographic volumes Racconti metropolitani (Metropolitan Tales) (2002) and Folletti (Sprites) (2003). His book of memories and observations about photography Il flânueur detective. Tra fotografia e racconto i ricordi degli anni più belli (Strolling detective. Photographs and memories of the best years) was published posthumously in 2015, edited by Marsilio.

He died in 2011 in Muslone di Gargnano on Lake Garda.

FAMILY

“I grew up in Venice, in a family where from my early days I always watched the adults writing, from morning to evening.”

Giulio Obici grew up in a family of intellectuals, journalists who were members of the socialist party and, during the war, of the antifascist Resistance.

Giulio Obici grew up in a family of intellectuals, journalists who were members of the socialist party and, during the war, of the antifascist Resistance.

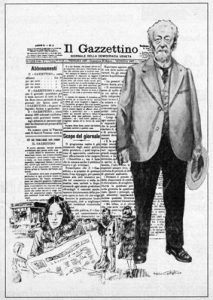

Great-grandfather on mother’s side is Gianpietro Talamini who, in 1887, started and managed the daily newspaper of the North-east Il Gazzettino. Grandfather Ennio who took over the management of the newspaper in 1934 after the death of his father, was expelled by the fascist regime from his role as director as well as proprietor of Il Gazzettino. A judicial process that took nearly fifty years, finally returned most of it to the heirs.

Mother Carolina, also a journalist, wrote for the La Lettura, while father Mario from whom Giulio inherited his passion for photography, carried out the task of main editor of the Gazzettino. He gave this up in 1944 when the Nazis occupied Venice and took control of the press. Mario Obici was never re-installed at the newspaper which in the years after the war entered into the sphere of the Christian Democrats.

Grandfather on father’s side is the famous psychiatrist Giulio Obici, standard-bearer of the Basaglia method and supporter of the Socialist party. Head of the psychiatric hospital of Venice, he banned the use of restraining beds and shackles during the first years of the twentieth century. After his death on 25 January 1906, the Avanti! Newspaper remembers him thus:

“Yesterday, at the age of only 37, Prof. Giulio Obici died after a short illness. He was the excellent psychiatrist and vice-director of the asylum San Servolo, someone on whom rested very high hopes for the new psychiatric science. He was a real original scholar, a brilliant and eloquent speaker, and in Venice, in only three years he became popular and universally appreciated and admired. He really was one of our best; the enormous work he did in reorganising San Servolo and the important studies he carried out but which prevented him from taking part in the militant life of the party to which he remained faithful all his life. He was the one who, in Ferrara and with other valued friends, started the local party and the paper La Scintilla”.

“Yesterday, at the age of only 37, Prof. Giulio Obici died after a short illness. He was the excellent psychiatrist and vice-director of the asylum San Servolo, someone on whom rested very high hopes for the new psychiatric science. He was a real original scholar, a brilliant and eloquent speaker, and in Venice, in only three years he became popular and universally appreciated and admired. He really was one of our best; the enormous work he did in reorganising San Servolo and the important studies he carried out but which prevented him from taking part in the militant life of the party to which he remained faithful all his life. He was the one who, in Ferrara and with other valued friends, started the local party and the paper La Scintilla”.

HIS PASSION FOR THE LEICA

“I learned writing between the ages of 8 and 10 and I learned photography when I was 20. I came to both of them a bit late but I have no regrets about that.”

“The Leica III came into the house in 1938. Including the lens it was the fantastic sum of two thousand and three hundred lire. If I think that my father in those days earned around two thousand lire per month, I can imagine that he wanted to carry it around his neck. He was a very good photographer: he loved portraits and landscapes (…) One of his prints, the boat with bathers on the beach at the Lido under a threatening sky (he told me he had used the green filter) has been framed and hangs in my sitting room: also as a token of gratitude.”

PHOTOGRAPH

“I wrote publicly, but I took pictures privately: my writings were totally on display and I therefore never thought or wanted to show my photographs. However, that does not mean to say that I practiced photography in order to turn it into a private diary: that would have been rather amateurish. You might say, what an idea: someone who takes pictures without making a profit, is always an amateur. That is not true: the professionalism of whatever intellectual activity does not depend on its remuneration. Above all, it is a way of working (…) Photographers are not divided into professionals or amateurs, but whether they are good or not so good.”

“Talking about photography, I have always been interested in reflexions, images which are multiplied on a mirror or in a window: there is always an optical surprise that contains a mystery. I also like what is behind it all: it is never certain whether it reflects reality or the opposite, the plot of a real story or of an imagined one. As in the theatre, where artifice puts the obvious reality of people as a counterbalance to the literary pretence and where the coup- de-theatre nearly always happens again. In other words, the overturning of certainties, the metaphor of life.”

“In photography, the creative process is complicated particularly because it is elementary, arduous because it is instant, uncertain because the first and the lasting do not arrange preparatory or desktop exercises (…). Paradoxically, but not always, one could say that photography is the least manual of the arts and can give mankind ample space to speculate.”

“Photography is nothing more or less than something which in an instant is already history, something which has come across the lens of the camera. This belief, as far as I am concerned and as far as it may be interesting, makes me print the whole negative. Nothing is cut, what is there must come out on paper. If there is more on the film than I had foreseen, I will never enlarge it: the picture has not been a success. The inevitable result is knowing that the photograph is “made” when you press the button, that it is exactly what you saw in the viewfinder or what you wanted to see.”

“Roland Barthes, in La chambre claire (Camera Lucida) maintains that “in every photograph” returns “that vaguely frightening thing” which is “the return of death”. I, on the other hand, when I look at whatever photograph of many years ago – for example a street scene from the beginning of this century – I immediately ask myself where that person, beautifully dressed, was going in haste up some steps, what he was saying to his friend by his side, where he was going from there and how the day would end. The opposite of death: the photograph relives the life as lived, the past, and gives it an indefinite and long lasting presence, the restraints of time vanish and it becomes immortal.”

JOURNALISM

“Giulio was first and foremost a great journalist, a great envoy, in the time in which envoys found themselves sent off, like extinct dinosaurs – and like dinosaurs – not expecting it. He had a great understanding of politics, could analyse it and speak about it. The concept of a scoop was foreign to him; in those years with all the havoc, the plots, the anti-state, he did not want to work isolated from his colleagues: instead, taking into account that he had the same details and information as all the others, the good journalist would have distinguished himself by being able to reorganise and describe them more completely or simply differently from the others (…). When I got to know him in 1973, judge Giovanni Tamburino in Padua had started the investigation on the entanglement between fascists, putschists, officials and devious heads of the secret services, which became known as “Rosa dei Venti”. The core of those who had been invited descended then on Padua, remained there without interruption for months, but he had already got together with others, elsewhere, following the first inquests and with Giulio were Marcella Andreoli of Avanti!, Gianni Flamini of Avvenire, Giuliano Marchesini of the Stampa, Marco Nozza of the Giorno, and none of these would have dreamed of tripping up their colleagues, hence: every bit of political information that one of these had obtained, had to be shared with all other colleagues, even those who did not strictly belong to this small group.

So if one of these others had given in to the temptation to withhold information or to distort it, in other words to betray the collective spirit, they knew that from that moment on they had to work by themselves. In all this Giulio was the guiding light. He presided over the afternoon meetings that took place in whatever hotel to exchange news and to extend the “stairs”. It was always him, vehement when angry, who knew how to confront incorrect colleagues and remove them from the pool, telling them to their face, why (…). Soon after that came the years of red terrorism and in Padua the 7th April inquest which was led by the substitute attorney Pietro Calogero on “Organised Autonomy” and its connections with the Red Brigade. The circle of those who had been there before returned, but in larger numbers. The choice of how to divide the news had not changed but had become more difficult, the political-journalistic option to get involved “against” subversion which had been so easy when it meant going against the neo-fascism, but now a few faltered. Friendships and old acquaintances deteriorated, but those that remained intact became stronger. They worked amidst attacks and personal threats. Giulio continued to encourage the group and it was he who obtained and shared the larger part of the news items. However, the splits became more frequent and his sharp rebukes as well.” (Michele Sartori)

“As a journalist I have followed the entire event of the Red Brigade (…) I remember that period as a time of enormous professional and civil commitment (…) also because, as someone on the left, I immediately assumed contrary positions, little inclined to pander to the flood wave which, also after the seizure of Moro, poured out a tide of rants onto public opinion and tried to accredit an anti-system vocation to the Red Brigade. I have never believed in that vocation and, after 1974, with the arrival of the new Red Brigade of Moretti and his associates, I was convinced that this terrorism was more a crutch of the system, a prosthesis invented or used to sustain the status quo and to hold back a natural evolution towards the goals of the left.”

PHOTOGRAPHY AND JOURNALISM

“In my life as a journalist I have followed an infinity of processes. I have never been an aseptic spectator: every time my writings followed my convictions and nearly always hit the most appropriate critical point, as was the case of Valpreda, just to mention one. But never, not even when it was no longer prohibited, did I go back, with block notes or the camera: the journalist follows the plot, the photographer stalks the episode. In fact I left my Leica at home, not only when I had to go to court but in every other part of my work. Possibly the only exception was the movement of Sixtyeight, but then the protagonist was the street and in the street there is space and time for precision and imagination. I have lost all the negatives of that time, but I religiously hold on to some prints and when I look at them it proves the formidable evocative power.”